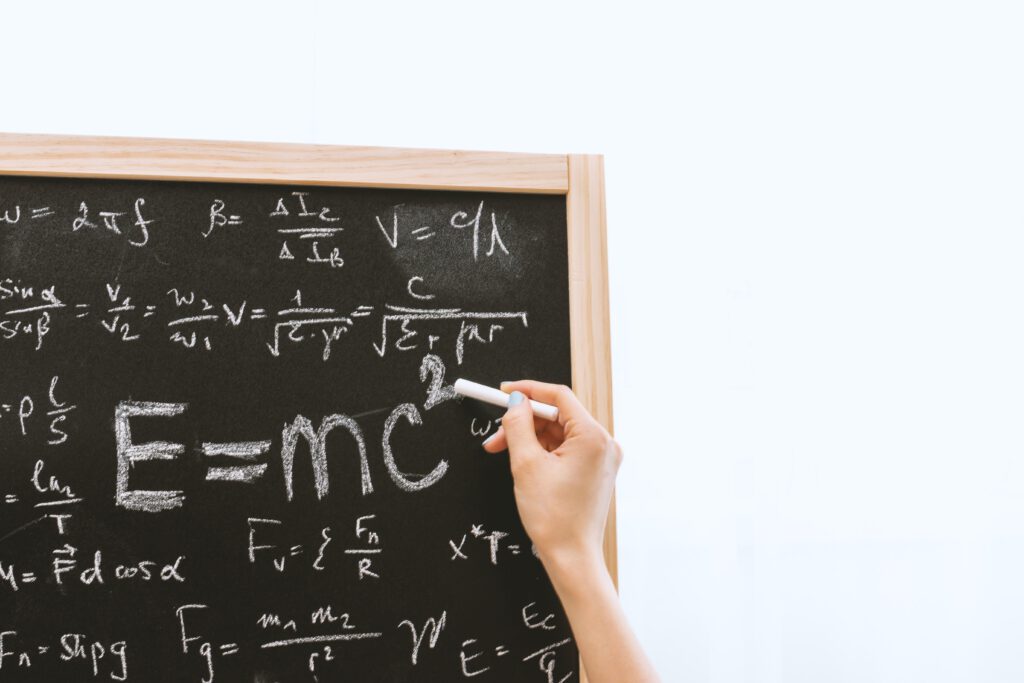

There is a fundamental difference between remembering something and understanding it. For me, mathematics is a great example of this. I can memorize a theorem without understanding its proof at all. This means I can maybe (barely) apply the general concept but have not succeeded in understanding the underlying principles.

The devil is in the detail

For many years, I thought having a rough idea of how a statement worked or being able to repeat it was sufficient, and the details were just that: details. Only after many mistakes and failures did I understand the error in my ways. Sometimes, the details are not just tedious chores but actually contain much of the inherent meaning. Once I got extremely inquisitive about every single detail and actually tried to understand the nuances in the statements I wanted to understand, my grades started improving, and I enjoyed mathematics more than ever. Things started making more sense, and there was an extra level of satisfaction to my studies.

Owning my opinions

Later, this diligence spilled into my other endeavors, and I kept asking questions way past the point where I would have been satisfied in the past. This made me feel more confident in discussions and made me more inquisitive and more open to changing my mind. Many of the opinions I held revealed themselves to be on shaky ground, and I started questioning my opinions more often.

This attitude helped me be more confident in my interactions with others because my strongly held opinions now had a factual basis to rely on, while I had an easier time admitting to lack of knowledge and my own mistakes (see my article on being wrong more often).

I also had an easier time questioning other’s opinions instead of simply accepting or rejecting them. Similar to my article on stubbornness, I improved on keeping an open mind while at the same time being critical of the points I wasn’t sure about, adding an extra level of nuance to my understanding of other people’s opinions.

We can easily step into the fallacy of sliding into opinions we haven’t actually formed. I know this has happened to me many times. It has become important to me to check my own opinions and make sure they are actually my opinions and not somebody else’s opinions that were eloquently conveyed and sort of made sense to me at the time.

Mistakes?

I have often had the experience of understanding advice people have given me only months or years after hearing it for the first time. I could have avoided many mistakes had I understood the advice I was given. Still, I do not regret making those mistakes because I think I needed to make some of those choices to learn to understand the advice given.

Maybe I could have avoided some of these mistakes if I spent more time thinking about the advice given to me. This is why I now try to really wrap my head around things that people tell me apart from just being satisfied with a shallow understanding.

Conclusion

If we get into the habit of mistaking remembering for understanding, we can slip into some nasty fallacies. Asking ourselves the question “have I really understood this statement in all of its facets?” can help us avoid many of them. Trying to understand things instead of slighting the details can help us make sure the opinions we hold are also opinions we formed.